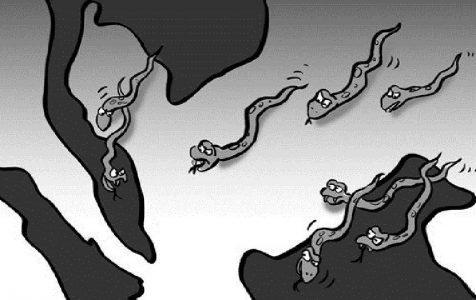

Infiltration of Islamic State into Southeast Asia brings lingering danger

On May 23, government forces in the Philippines battled with two terrorist groups affiliated with the Islamic State (IS), the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) and the Maute group.

Southeast Asian terrorist organizations loyal to IS can launch terrorist attacks on cities and conduct long-term confrontations with military forces. This shows the infiltration of IS in Southeast Asia has gradually deepened.

Indonesia recently witnessed a number of violent attacks, with IS claiming responsibility for some. Malaysia has arrested many people linked with IS. Thailand closed border crossings with Malaysia to prevent the entry of terrorists.

The current situation is pushing us to consider the influence of IS in Southeast Asia.

With the aid of online social networks, the extreme Islamic ideology advocated by IS is spreading rapidly in the region. The number of radicals is rising and some local terrorist organizations have resumed their vitality. What’s more, some emerging terrorist groups have been established and are showing loyalty to IS. The influence of IS in Southeast Asia is real and is on the rise.

IS has recruited members in Southeast Asia. Overall, Muslim groups there are moderate. But with the large number of Muslims, IS can easily find people who sympathize with or support IS.

The group’s main tool for propaganda and recruitment is social media. There are at least 1,000 Facebook accounts supporting IS in the region. In June last year, IS released a video appealing to its supporters to focus on Southeast Asia, and join its regional branch in the Philippines.

In addition to local recruitment, IS also actively recruits foreign extremists who have fled to Southeast Asia. Lax border control in the region makes it easy for extremists to enter and hide.

IS has many branches in Southeast Asia. Some Southeast Asian militant groups such as the ASG have showed loyalty to IS and organized a loose alliance. Isnilon Hapilon, the leader of ASG, has been appointed by IS as emir in the region. Some experts said that up to now, more than 60 Southeast Asian militant groups have showed loyalty to IS. There is yet no specific information for these militant groups such as their size, composition or the methods IS uses to command and fund them. So people may doubt whether IS has the ability to organize its branches there.

However, there is something worth noting. On April 6, the Jama’at al-Muhajirin wa al-Ansar bi al-Filibin (JMAF) was formed, with the goal of coordinating overall IS strategy in Southeast Asia and accepting foreign members of IS. According to Malaysia’s counter-terrorism police chief Datuk Ayob Khan Mydin Pitchay, among the Malaysian people who participated in the terrorism attack in Malawi, there was one terrorist named Mahmud Ahmad appointed as an alternative of Hapilon. Once Hapilon is killed, he will act as a IS leader in southern Philippines. All these facts indicate that the organizational capacity of IS should not be underestimated.

At present, it seems that the local extremists in Southeast Asia are converging with IS, and IS is actively claiming responsibility for regional terrorist attacks. According to Rumiyah, an IS propaganda tool, IS has established an East Asian branch in the Philippines. Once IS forms a core area of terrorism in the south of the Philippines and attracts more terrorist organizations, extremists may regard this area as an alternative battlefield to the Middle East and launch more large-scale terrorist attacks. The shadow of IS will linger in Southeast Asia for a long time, and gradually become more established and dangerous.

Source: Global Times