What’s next for Hezbollah after the death of Qassem Soleimani?

The death of Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) commander Qasem Soleimani has caused aftershocks in the Middle East and farther afield. His assassination was surprising, with U.S. forces taking advantage of Soleimani’s presence in Baghdad to target his convoy with a fatal drone strike.

Since his death, despite aggressive rhetoric from Tehran and its allies, the military response has been limited; Iranian missile strikes against two Iraqi bases that host U.S. forces that caused no deaths have been the extent of the Iranian response (Middle East Online, January 7).

Long-term repercussions have taken precedence over the short-term implications, as both the United States and Iran have moved away from direct military confrontation. One of the most pertinent questions is what impact Soleimani’s death will have on Tehran’s most important proxy ally—the Lebanese political and militant force, Hezbollah.

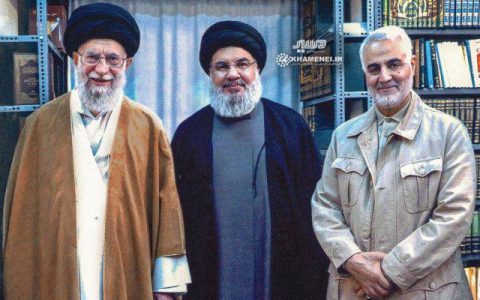

The relationship between Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah and Soleimani was well documented. In a rare television interview in October 2019, Soleimani recounted how he and Nasrallah were almost killed in an Israeli drone strike during the Second Lebanon War in 2006, while officials have spoken of their “unique and close” friendship (Middle East Eye, January 17).

Soleimani also had a close relationship with Imad Mughniyeh, a Hezbollah leader killed in Syria in 2008, and Mohammed Hejazi, who led IRGC forces in Lebanon. The three were at the heart of modernizing Hezbollah weaponry, with Tehran providing high-precision missiles under Soleimani’s direction (Jerusalem Post, January 22).

Soleimani described how he oversaw military operations in Lebanon throughout the 2006 conflict and was in constant communication with Tehran and Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (Asharq Al-Awsat, October 3, 2019). Hezbollah has remained under the direction of Soleimani and IRGC forces, with Nasrallah taking direction from Tehran.

Soleimani coordinated Hezbollah’s intervention in the Syrian war to ensure pro-Iranian President Bashir al-Assad reasserted power over large swathes of the country while also ensuring a permanent presence for both Hezbollah and Iranian forces in south-western Syria (Asharq as-Awsat, October 2, 2019). A second front against Israel is one of many converging military goals for Hezbollah and the IRGC.

Hezbollah is a vital component of the so-called ‘axis of resistance,’ also composed of the Syrian Assad government and Iran. Out of all of Iran’s proxy allies, including Hamas in Gaza, the Houthis in Yemen and Shia militias in Iraq and Bahrain, Hezbollah’s military and political clout make it Iran’s greatest regional ally.

Hezbollah benefits from significant material, financial, and tactical assistance from Tehran, with the IRGC’s ability to send supplies extended in recent years by the expansion of the land corridor from Tehran to Beirut, utilizing its allies in Baghdad and Damascus to protect supply chains (Arab News, June 13, 2017).

Nasrallah’s rhetoric in the aftermath of Soleimani’s death was predictably fiery. Nasrallah claimed that Hezbollah would “raise his [Soleimani’s] flag in all battlefields” and there would be “retaliation against the American military presence in our region” (Islam Times, January 3). This sort of adversarial reaction was largely symbolic and intended to show solidarity with Tehran. Despite this reiteration of commitment, the promise of reprisal killings has not emerged in reality.

There has been no internal movement against U.S. troops or assets within Lebanon. In reality, the United States only has a minimal security presence in Lebanon, limited to low-level troop deployments in two Lebanese sites (The National, January 11). The scope for retaliation against such bases is negligible, owing to the potential for Lebanese civilian or military casualties.

The United States also trains and equips the Lebanese Army, which is separate from Hezbollah’s military wing. This is largely due to the fact that the United States views the regular armed forces as a counterweight against Hezbollah’s military might.

In the long term, Hezbollah is likely to continue its campaign of disrupting, restricting and intersecting the United States and its allies’ military operations near Lebanese borders, but Nasrallah’s bellicose rhetoric has proved to be nothing more than symbolic resolve with Iran. Some evidence of troop movement near the Israeli border has emerged, but this is normal practice.

Reciprocal, but low-level, acts of aggression with Israel are credible, but the likelihood of direct confrontation targeting U.S. assets became minimal after Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif said Iran’s response concluded with the missile attacks on the U.S. bases in Iraq (Tehran Times, February 15).

A large part of this rationale is that Hezbollah does not want to get drawn into a regional conflict at this juncture due to the domestic political situation in Lebanon. Since October 2019, the country has been rocked by large-scale anti-government protests, with activists demonstrating against a corrupt political elite and spiraling economic crisis (Arab News, January 19).

Nasrallah has spoken of his concern of an impending economic collapse, an event that could heavily impact Hezbollah’s domestic standing. While Hezbollah’s military strength stems from Iranian assistance, its political strength depends on domestic support.

Hezbollah leaders have agreed to be part of a technocratic government, after resisting the move for numerous months as it limits its own power within the governing coalition. The need to stabilize the domestic political situation has taken precedence over any military response to the death of Soleimani.

Despite huge rallies denouncing the death of the Iranian commander, the majority of the Lebanese population favors the resurrection of a functioning government and economy over military engagements; any action by Hezbollah would be perceived as further threatening internal stability. The group has to secure its own position in Lebanon before pursuing external activities.

Internationally, Hezbollah has to balance its ideological commitment to Iran without provoking a reaction from the United States. A military response to Solemani’s death would risk inciting a response from the United States; the imposition of punitive sanctions would have a devastating impact on the Lebanese economy.

Nasrallah’s promises of retaliation included no firm commitments to military engagement, with the Hezbollah leader likely deliberately keeping his rhetoric vague to avoid drawing U.S. ire. The new technocratic Lebanese administration has reiterated its pledge that the government will have no confrontational position towards the West.

In the short term, Soleimani’s death will have limited impact on the overall direction of Hezbollah. Nasrallah’s position as an influential Shia leader will likely expand in the region, and the secretary general will continue to take tactical and material direction from Tehran. The structure of coordination between the axis of resistance will continue unabated, although an immediate military response targeting U.S. assets appears highly unlikely.

Once stability has been regained domestically, Hezbollah might begin to pursue a military response and escalate hostilities between itself and the United States and Israel. Troop movement near the border with Israel is commonplace, and the resumption of reciprocal attacks targeting the Israel Defence Force (IDF) is highly likely.

Hezbollah remains committed to the removal of all U.S. bases in the Middle East and limiting U.S. influence in the region, in line with the strategy dictated by Tehran. These long-term goals are highly unachievable without military intervention and it is possible there will be a drift toward conflict with the United States. The death of Soleimani will likely act to harden Hezbollah’s anti-U.S. resolve, but in the short term, any military response is unlikely as Hezbollah attempts to regain domestic stability.

Source: James Town