Teenage Terrorists Are a Growing Threat to Europe’s Security

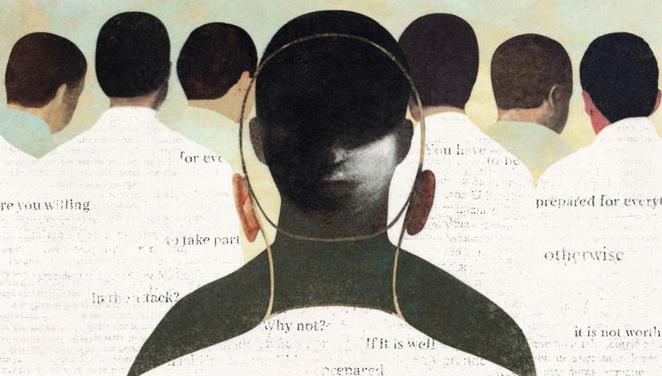

Terrorists in Europe are getting younger, and authorities are struggling to find them.

In recent months, dozens of adolescents as young as 14 have been arrested across Europe for allegedly plotting attacks against music venues, shopping centers and sites of worship.

A 14-year-old girl from Montenegro was arrested in Austria in May last year for allegedly plotting an attack on “nonbelievers.” The police seized an ax, a knife and Islamic State propaganda from her house. Another 14-year-old was arrested in February for plotting to attack a train station, Austrian authorities said.

Three Taylor Swift concerts in Vienna were canceled last year after three suspects ages 17 to 19 were arrested for conspiring on what the Central Intelligence Agency called a “well-developed” plot that could have killed hundreds.

Young people are increasingly drawn into online communities that propagate extremist views, conspiracy theories and violence. While the U.S. has long had a problem with school shooters, the growing teenage threat to Europe comes primarily from Islamists.

Behind the teen extremism crisis lies a combination of factors: an unprecedented spread of extremist propaganda accelerated partly by artificial intelligence; the powerful hold on youths by social media such as TikTok with increasingly sophisticated means of retaining user attention; and events such as the Gaza war, which has become a defining, and painful, political moment for a generation gaining political awareness.

Teenagers made up two-thirds of the 60 Islamic extremists who were arrested on terrorism charges across Europe in the first eight months following the start of the Gaza war in October 2023, according to Peter Neumann, professor of security studies at King’s College London, who researched that period for a book.

Europe’s young far-right is also a growing threat. Belgian police in January arrested a 14-year-old boy with neo-Nazi views on suspicion of planning an attack on a mosque.

One-third of Belgian terrorism cases from 2022 to 2024 involved minors. In Britain, nearly one in five terror suspects are children. Terrorism arrests declined across all age groups in the U.K. during the pandemic, with one exception: children.

“What is new is the number of youths that are directly involved in plotting violent attacks, and that includes very young individuals,” said Thomas Renard, director of the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism in The Hague.

Almost all young extremists are radicalized online, experts say, making it harder for authorities to spot them.

In the past five years, 93% of fatal terrorist attacks in the West were perpetrated by lone-wolf actors, according to the Institute for Economics and Peace, a think tank. The internet has accelerated radicalization. According to the institute’s Global Terrorism Index, it took a person on average 16 months to radicalize in 2002. In 2015, the period had shortened by 40%. Today, it may take just a few weeks.

Online, ideology is fluid, and extremist views that share central tenets, such as misogyny and totalitarianism, often blend, experts say. Young white supremacists admire the doctrine of Islamic State. Young jihadists borrow the language and aesthetics of the far-right. Rather than issue orders, terror groups flood social media with propaganda that gives young people an ideological framework and inspiration to carry out attacks, experts say.

A Gen Z extremist

An example of the kind of extremist that European authorities are worried about is currently on trial in Belgium.

For Abdul Kerim Gadaev, a 19-year-old Chechen refugee, his father’s deportation to Russia from France four years ago is still a source of anger. Following the deportation, Gadaev became alienated at school. Online, he aired his desire to replicate the 2015 Bataclan attack in Paris that killed 90: “A Bataclan 2.0,” a Belgian public prosecutor alleged last month in court.

Belgian police last year arrested Gadaev and three other suspects ages 15 to 17. On Gadaev’s phone, investigators found evidence that he researched the Bataclan attack, the 2015 attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris, and Abdoullakh Anzorov, the 18-year-old Chechen refugee who in 2020 decapitated a French secondary school teacher. They also found a photo of the teacher’s severed head.

As he was questioned in court last month about posting hateful content on social media, Gadaev grew fidgety. Sporting a wispy full beard without a mustache, he nervously scratched his wrist behind his back and pulled his sleeves over his hands. “I didn’t think I was doing anything wrong,” he said.

The radicalization of minors contributes to a growing terrorism threat facing the West. The number of completed, failed and foiled terrorist attacks in the European Union quadrupled from 2022 to 2023—to 120 incidents—according to the bloc’s law-enforcement agency, Europol.

While many attacks are prevented, terrorism-related deaths in the West rose by 61% from 2023 to 2024, and the number of successful attacks roughly doubled to 67 over the same period, according to the Global Terrorism Index.

U.S. government agencies don’t provide data on the age of suspected terrorists, but the trends in right-wing radicalization in the U.S. are similar, experts say.

“Whereas Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan were the main exporters of jihadi ideology, the U.S. has become one of the main exporters of far-right ideology,” said Renard, the director of the Hague-based think tank.

“The online environment provides ample opportunities for terrorists…to connect to young people in seemingly innocuous social media applications and gaming platforms,” an FBI spokesperson said.

Following no leader

With only a superficial understanding of ideology, most young extremists initially find an attraction to violent narratives online, driven by individual grievances and vulnerabilities, such as psychological distress, loneliness and marginalization, experts say. Online, they find a community around collective crises and traumatic events, such as fear of migration or the war in Gaza, which they connect to their personal struggle.

“People associate themselves with the suffering. And they want to do something about it,” said Kevin Volon, spokesperson for Belgium’s Coordination Unit for Threat Analysis, a governmental center that analyzes extremist threats. Groups of young radicals usually organize online without a formal leader or religious authority. “The extremist landscape is really decentralized,” Volon said.

In Chaudfontaine, a small Belgian municipality where Gadaev settled with his stepmother after his father’s deportation, the teen fell behind in school. He found an online community around sports and religion, particularly on TikTok, where his circles became increasingly political.

“I was on my phone 24/7,” he said.

In February last year, he joined an “operational” channel on the encrypted Signal messaging app where members started plotting an attack, according to the prosecutor. Some as young as 13, they discussed how to acquire weapons and shared photos of the target, the Botanique, a concert hall in central Brussels. Gadaev said he was willing to participate as long as the attack was well prepared.

In March 2024, Belgian federal police arrested Gadaev and three others, all minors, across Belgium. French police also arrested three minors in connection with the case. The six underage suspects are handled by the two countries’ juvenile systems, away from the public eye. The Belgian prosecutor is asking for a seven-year sentence for Gadaev.

Gadaev’s defense attorneys said his rhetoric on social media was “performative.” The argument speaks to the challenge facing Western intelligence agencies: how to discern when hateful speech may tip into action.

“We have been saying for some time that the complexity of our investigative casework is like never before, the breadth and depth of what we are dealing with is extraordinary,” said Vicki Evans, the U.K.’s senior counterterrorism policing coordinator. She called on tech companies to help tackle the problem.

Social-media algorithms create a pull effect on young people by suggesting increasingly violent content and creating digital rabbit holes. Artificial intelligence has exacerbated the problem, said Julia Ebner, an expert in online radicalization at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue think tank and the University of Oxford.

“AI generated videos and images tap in to very deep emotions and into human nature,” she said. “AI and the algorithms are partly doing that job of a charismatic recruiter, just a hundred times better.”